The sound of the anchor chain clunking into the cogs as it came up from the depths stirred me awake early, and I’m so glad it did. After throwing on my down jacket, I stepped out of the warmth of my cozy cabin and onto the deck, where the blast of a cool outflow breeze hit my face. I smiled. Despite the summer-like conditions we’ve experienced so far on this trip, we were heading to my favorite place in Alaska: Dawes Glacier. I have a thing for ice.

A Landscape Sculpted by Time and Ice

The view from the wooden deck is breathtaking, to say the least. A glimpse of what is to come hung on the ridgeline in the distance: Sumdum Glacier, beautifully visible in the morning light. Now only a fraction of its original size, these glaciers are the powerful forces behind the landscape that has shaped this incredible coastline.

Photo: Jeff Reynolds

Sumdum Glacier hanging in the background of Wood Spit, a terminal moraine formed thousands of years ago by Dawes Glacier.

During the last ice age, over 16,000 years ago, most of Alaska was covered by two miles of ice. Glaciers slowly carved out spectacular valleys and fjords, one of which we were currently traveling down in a 112-year-old, beautifully converted wooden tugboat. Dawes Glacier, the one we were heading 30 nautical miles up Endicott Arm to see, once extended this far out. It pushed rocks, gravel, and silt, digging out a massive “gully” up to 1,000 feet deep in some places, leaving behind a picturesque terminal moraine called Wood Spit, where we had conveniently anchored the night before. You can’t look around at Alaska’s landscape and not see evidence of how glaciers sculpted this place—it’s everywhere.

Is this the right glacier? Let me know if you have a better option V – This is not Dawes glacier but it was meant to be a view back at the ship because we were heading back. Meant for later in the article.

A Cold Welcome: The Approach to Dawes Glacier

As the ship steamed further up the fjord, it grew narrower, and the air got colder, as if we were entering a gigantic freezer. The mass of ice that makes up Dawes Glacier begins with the Stikine Icefield at an elevation of 5,200 feet (1,585 meters). From this source, the ice flows slowly—about 15 feet per day—along the path of least resistance. Multiple tributary glaciers feed into the main tongue, like streams into a river. This mass of ice cools the air around it, and the cold, dense air stays within the confines of the fjord, flowing outward.

The first visible sign that there’s a tidewater glacier ahead of us is the presence of small pieces of ice, looking like sculpted crystals, floating by the ship. These aren’t icebergs—these are mostly bergy bits (1-5 meters in size) or growlers (<1 meter in size). They’ve crumbled off the face of the glacier into the water and are flowing out with the wind and tide.

Photo: Jeff Reynolds

An iceberg floats by the ship on our way up Endicott Arm, hinting at what lies ahead.

Once we get even closer and round the final bend in the fjord, the glacier comes into full view in all its crevasse-ridden glory. What strikes me first, besides the heavenly blue colour, are the dark stripes flowing lengthwise down the glacier. These are signs of the tributary glaciers that flow into the main glacier. Along the outside edges of glaciers, they carry rocks and sediment that fall or scrape off the cliffs onto the surface of the ice, creating artistic streaks when they join the main glacier.

Photo: Simon Ager

Dawes Glacier comes into view with its dark medial moraines from tributary glaciers running the length of the glacier clearly visible.

Why is Glacier Ice So Blue?

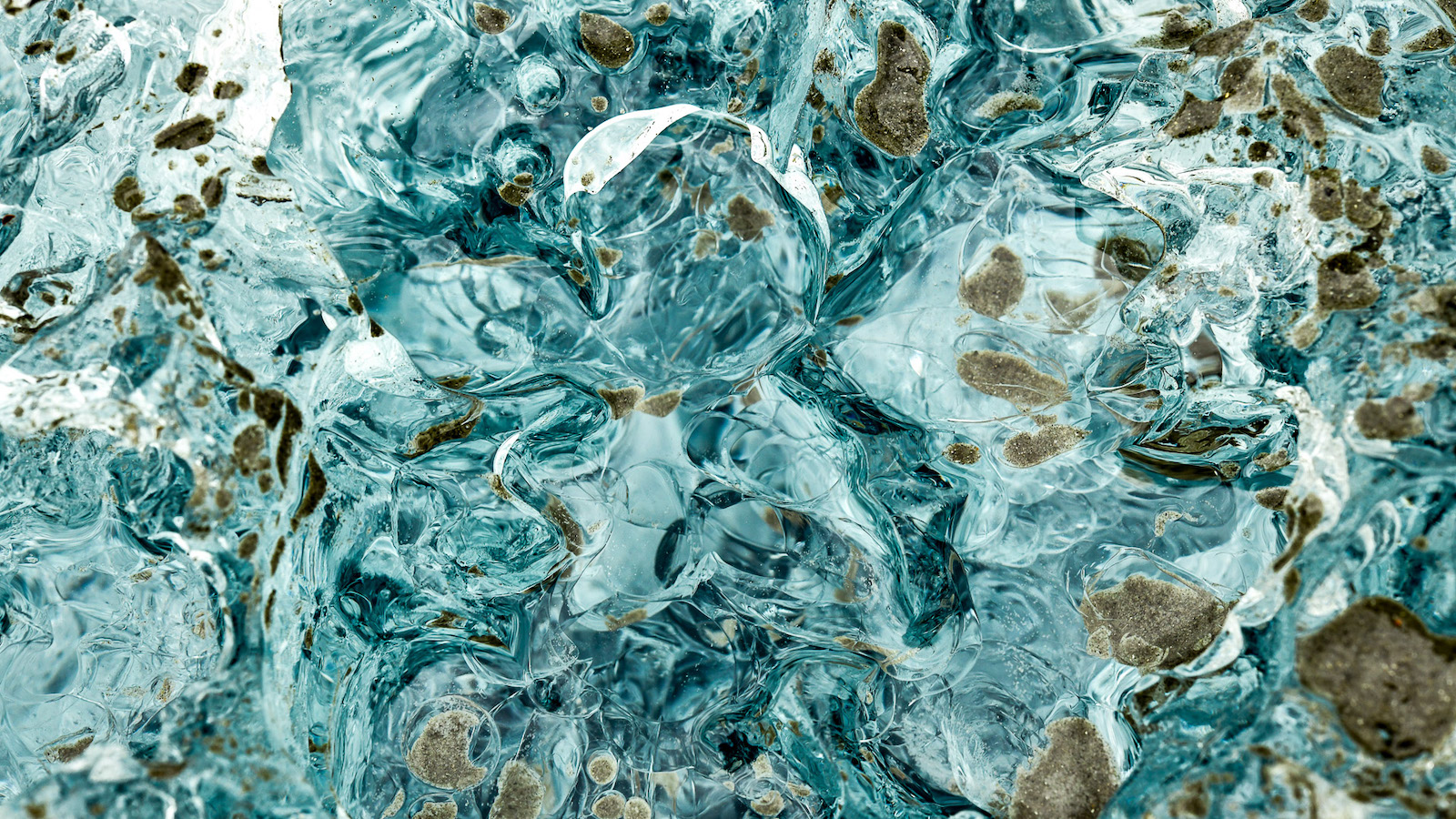

The ice in the water begins to get denser the closer we get to the glacier. This makes navigating these waters in a wooden tugboat a bit challenging, so we all board the tender to get closer to the great wall of ice in the distance. As we meander through the beautiful blue-coloured icebergs, the sound of ice hitting the aluminum hull echoes. I then answer the question everyone is dying to know: Why is the ice blue?

Water and its frozen form, ice, have a similar effect on light, in that they trap long wavelengths of light, such as red and green, while allowing the shorter wavelengths, like blue, to pass through the ice and reach our eyes. That’s why the blue colour is most visible in shaded areas, not in direct sunlight. The light passing through the ice appears blue, but the directly reflected light off the air bubbles in the ice appear white in colour.

Photo: Simon Ager

Glacier ice appears blue because dense ice absorbs every other colour in the spectrum—only blue light escapes.

When Ice Surrenders to Gravity

As we get closer, the tender pushes through denser and denser ice, and we notice how our eyes have to keep looking higher and higher as the true size of the glacier’s face begins to reveal itself. Hundreds of feet tall, the jagged, brittle-looking front is now in full view. What shocks everyone is just how loud it is. Yes, loud! I’m not talking about the sound of calving, but rather the sound of a white noise machine turned up to maximum volume. It’s the sound of a melting glacier—the sound of trillions of ancient air bubbles popping as they escape from the ice as the face melts in the warmer ocean water. It’s a breathtaking sound that envelops us all.

Photo: Jeff Reynolds

The tender making its way slowly through the dense ice floes with Dawes Glacier up ahead.

Just as we’re being hypnotized by the popping bubbles, a thunderous sound erupts in the distance. A tower of ice the size of a school bus breaks off the face of the glacier and crashes into the sea, spraying water and ice in all directions and sending a giant swell toward us. We simply float over it and marvel at the sheer power this glacier has.

Photo: Jeff Reynolds

Ice shards and water explode from the sea as tonnes of ice crumble off the face of Dawes glacier.

Life on the Edge of a Frozen World

An interesting observation is just how much life exists right at this frigid boundary. Arctic terns and gulls are seen plunge-diving for krill and small fish along the turbid edge of the glacier. Harbor seals seek refuge from predators by hauling out on icebergs, and mountain goats are traversing the steep terrain to access the salty algae along the shoreline— a rare sight to behold.

Photo: Jeff Reynolds

The steep cliffs that make up this fjord don’t make it easy for these Harbour seals to haul out on land so they utilize the next best thing, ice!

I love the energy that accompanies glacial regions like this. It seems to infect us all with a new sense of wonder and appreciation for this incredible planet, and makes us feel incredibly small. Alaska is lucky to have these tidewater glaciers, although, since I first started visiting Dawes Glacier, I’ve watched it recede by over 1.6 miles (2.5 km) in just the last decade. Many of Alaska’s tidewater glaciers have been experiencing significant retreat, though a few have managed to remain stable or even advance.

The time has come to return to the ship and warm up with a delicious hot chocolate and a delightful meal back on Swell, as we start our journey back out the fjord, moving with the ice and the cool breeze flowing off the glacier, and looking forward to what tomorrow brings.

Photo: Fred Catroll

Adventure set to glacial proportions! Exploring the icy wonders of a glacier up close is just one experience you can expect on expedition with Maple Leaf.

Photo: Jeff Reynolds

The warm and welcoming MV Swell awaiting her passengers arrival back with the smell of the next meal wafting throughout ship.

If you’ve dreamed of witnessing Alaska’s tidewater glaciers and all that comes with it, now is your chance. Join us aboard Swell—or for the first time in a decade, Maple Leaf—for a far-out journey in remote wilderness, where towering ice, abundant wildlife, and the stories of the land come to life. Experience these fleeting wonders before they retreat even further—because some adventures can’t wait.