By Maureen Gordon, with reports from Greg Shea, Matt Whelan and Kevin Smith

As an ecotourism company that actually owns its own boats, we do almost all of the work to maintain and upgrade them ourselves. This gives some of our crew employment throughout the winter, and gives them a deep understanding of the vessels, their stories and their capabilities. Next time you’re on a trip, you may find that wonderful person who just poured you a glass of wine also understands how every system behind the scenes is plumbed, wired or built.

This 3-part series from the winter of 2019-20 provides a snapshot of what happens to these ships under the cover of a west coast winter.

Part 1 Maple Leaf: A Once-in-a-Lifetime Project Renewing the Bow

When you take apart the planks on a wooden vessel, it’s like pulling back pieces of time.

This year, the Maple Leaf’s crew delved deep into the ship’s past, as they performed one of her major life projects: the examination and renewal of her bow. Captain Greg Shea led the project, similar to one he led on her stern in 2014.

We plan projects like this well in advance, as they are extremely costly and time consuming. They require special shipwright and carpentry skills as well as materials you don’t find sitting on the local lumberyard’s shelf.

There is a saying that ships are the nearest thing to dreams that hand have ever made. This is especially true with classic wooden ships. Nothing on them is from the factory, everything is unique and done by hand.

Here is the story of Maple Leaf’s 2019-2020 bow rebuild.

November 2019, Victoria, BC: Setting Off

Last November, as soon as we decommissioned Maple Leaf from her final Gulf Islands National Park trip of 2019, the crew loaded her and our truck-and-trailer with the woodworking tools we keep in storage, then untied Maple Leaf’s lines and set off again.

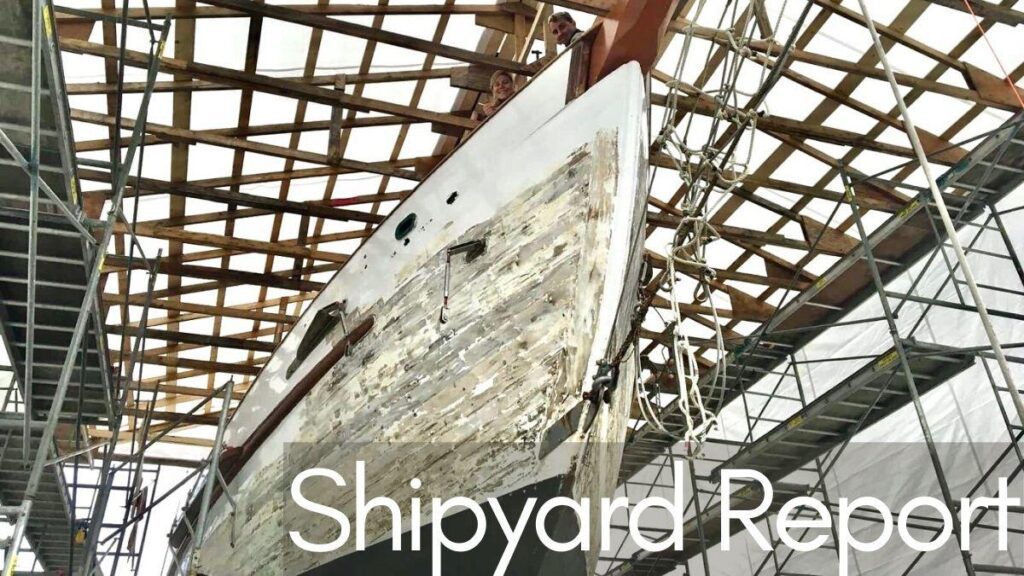

They sailed her across Georgia Strait and partway up one of the Fraser River’s arms, to our shipyard in Richmond. There, we hauled her out of the water with a travel lift, which wheeled her across the tarmac to a space in front of our shipwright, Commodore’s Boats. There, for the next 6 months, our crew, with assistance from Commodore’s shipwrights and shipwright Keith Battersby from Victoria, would work on the ship.

The First Month, Richmond, BC: The Prep

- The Shed: Before they started on the ship, the crew had to build a shed to protect her. So part of November involved ‘house construction’ and some views from high up in the rafters, above the Maple Leaf’s deck.

- De-rigging: Before the crew took the bow apart, they had to remove all the things it holds up …like the bowsprit. The team unfastened the sprit from the foredeck and the foremast, refastened the foremast stays, and, with a hydraulic crane, pulled the bowsprit out for storage.

- Opening the Bow: Finally, the crew lifted off the mahogany rails that ‘cap’ the bulwark, which is the ‘side’ of the ship. Then, starting at the bottom, they took off the surface planks to finally unveil what kind of a job this project was going to be.

Winter, Richmond, BC: The Examination, The Stem & Planking

“We didn’t know for sure how much we’d be doing,” said Greg about the level of work that would be required. “When we got into the structure of the boat, I realized it was in great shape – much better than I would have thought.”

In the end, they replaced the stem, all the stanchions, and a few frames as well as planking.

Through the month of December, they slowly and carefully exposed the entire bow area and examined it in detail.

If you’ve dined on Maple Leaf, you may enjoy conjuring an image of Greg and one of our mates, Dan, eating their lunch on exposed frames eight feet up, with only air around them, and the tarmac of the shipyard far below.

In this period, they replaced the stem. The stem is the most important piece of the bow and this job is the most challenging part of the whole project.

The stem is ‘the pointy end’ of the ship, a large and incredibly strong piece of wood where all the planks come together and fit into rabits (grooves). It runs vertically from the keel to the top of the bulwarks. It literally holds the ship together.

As important as it is, the piece of wood used to create the new stem is carefully chosen – and very carefully worked from raw lumber into finished part.

“It’s an unbelievably valuable piece of wood,” said Greg. “You can’t make a mistake.”

The stem was a 16-foot by 20-inch by 24-inch piece of Douglas fir that was air dried for eight years in the Commodore’s Boats shop, making it tough and flexible. This single piece of wood had already cost $6,000 before the first swipe of a tool, and the first second of work, touched it.

Shipwright Brendan, a master craftsman in woodworking who was trained as a shipwright in Scotland, designed the pattern of Maple Leaf’s raked stem, and shaped and cut it out of the wood, larger than it needed to be. He began fairing it in slowly, closer and closer to fitting into Maple Leaf’s bow. After it reached a certain state, Maple Leaf crew members with skill in woodworking were able to continue the work to completion.

Spring, Richmond, BC: Frames and Planks and Re-rigging

The crew replaced a few of Maple Leaf’s frames (the ribs) and quite a few stanchions, made from yellow cedar.

They also replaced the outer planks. These incredible pieces of wood are edge-grain Douglas fir from British Columbia, air-dried to keep them flexible. Each is between 20 and 30 feet long, 8 to 12 inches wide and 2 to 2.5 inches thick, from stock the shipwrights keep on hand. It’s a woodworker’s dream to review the pieces in this shop.

“When they pull the really big boards out,” Greg said, “I often take a picture or just drool a little bit. It’s hard to find wood like that these days.”

To create the planks for Maple Leaf’s bow, each is first shaped by a shipwright, then attached to the ship. Attaching the boards is complicated. It’s not about holding a plank against a frame and pounding a nail in. For each place that you attach a board to the ship – and there are six thousand of these – you do this:

- 1. Pick up scrap pieces of wood discarded in the shaping, and cut plugs to be used later.

- 2. In each location on the board where you want to fasten it to the frames, drill a wide hole in just the top layer of the wood for the plug. The plug will be the last thing to go in.

- 3. Next, in the same place but going deeper, drill a pilot bit, which is an initial, small hole through which you’re going to put your fastener (e.g. a lag bolt, called a lag).

- 4. Wrap your fastener, a stainless steel lag, in cotton and then dip it in linseed oil.

- 5. Drive the fastener through the pilot hole and into the frame.

- 6. Now the wood is fastened to the frame, with a gap between the head of the lag and the outer edge of the wood, where you made the hold wider, for the plug.

- 7. Make an epoxy.

- 8. Take a plug, dip it in the epoxy and put it in the hole.

- 9. Now, you have a wooden plug on top of the stainless steel lag, but the plug is sticking out above the edge of the plank.

- 10. After the epoxy has hardened, cut off the part of the plug that sticks out from the plank, and sand it down to be even with the plank.

- 11. Repeat these ten steps, six thousand times.

After the planks are on, the shipwright and skilled crew applied ‘caulking’ to the seams, which, for a wooden ship, is made from tightly twisted fibres, first a layer of cotton, then a layer of oakum, both pounded in. To the outside of the seams, the crew apply a mixture of tight-ten Portland cement and a PVA glue over the caulking to finally seal the seam below the waterline, and above it they apply a marine adhesive for the same purpose.

Next, the team shaped the shear line, cutting away stanchions that protruded too high, to create the beautiful sweeping line we all love from the stem, down past the foredeck to the well deck. Meanwhile, other crew climbed up into the trusses of the shed over the ship, and sanded and varnished the cap rails stored up there.

The crew also performed regular maintenance tasks such as cleaning and scraping the hull, sanding and painting the hull, installing a sewage treatment system, upgrading the galley, and conducting Transport Canada inspections for fire, radio, life raft, and electrical systems. For several weeks, our tugboat Swell arrived, was worked on, and went back to Victoria.

Then, as spring flowers filled the air with pollen, the crew finally put the ship back together – cap rails back on, bowsprit back in and attached, stays re-fastened.

Finally, after months of a project so big that at times it was hard to see amid the many small and sometimes menial tasks, the shipyard lowered Maple Leaf back into the Fraser River.

It was the culmination of months of living in a shipyard, through sun, rain, wind and even snow. The momentous project cost six-figures and took the crew’s dedicated commitment to complete. At times a dirty job, at times a cold job, or a monotonous job, the work was made meaningful by the grace of the ship herself, the camaraderie of the people who work here, and the mission of what the ship and her trips accomplish. To us, the ship is more than a schooner that floats in the water, and her crew always have their eyes out for her.

“There’s nothing like being on a wooden boat,” said Greg. “The feel and the warmth of a wooden boat – it’s basically a love. I can’t say it makes sense, but there is something about it that’s just right.”

Layers of History

One of the most interesting parts of a project like this is the very tangible connection the crew feel to Maple Leaf’s past caretakers and those in the future they may never know.

“You think about the past, about who put it together,” said Greg about the work. “A person’s character is part of their build.”

The crew found square fasteners in the planks they pulled off, which haven’t been used for a long time. It’s possible some of them were attached back in 1943. They found different styles of work, and ingenious ways of fixing mistakes that are almost impossible to see.

It makes you see where you fit in the lifetime of a wooden ship, which, if properly cared for, continues on like cultural customs or ways of tracking time – handed down from generation to generation.

“We assume the work we replaced was 50 years old. We were doing it knowing we wouldn’t be coming back in our lifetime to do it again,” said Greg. “We were doing it knowing the ship is in amazing shape and has a full life ahead of it. We were doing it for the future.”

##

Special shout outs must go to Grace Van Helvoirt and Dan Baker, who put in the most work on this epic project, to Greg who managed it, and to Kevin Smith whose dedication to caring for all of the vessels ensures their long future lives.

Stay tuned for Parts 2 and 3, about Swell and Cascadia’s winter projects.